If you live in Manitoba, your income taxes probably increased in November without you noticing.

In the spring, the NDP government of Manitoba issued it’s second budget under Premier Wab Kinew. The Building One Manitoba Budget was released in March 2025, but the tax changes were not signed into law until November. The Budget includes “lowering costs for Manitobans” as a key theme, but it also includes something that will cost Manitobans — a removal of the indexing of income tax brackets.

This is sometimes called a hidden tax increase because it doesn’t involve explicitly increasing a tax rate. It works by eroding away your tax free income as inflation compounds over time. Increasing taxes without Increasing Taxes. (see EDIT at the bottom for more on how this works).

In this case, it is also “hidden” because the government made it difficult to find. There is no mention of it in the Budget Speech or in the Budget New Release or in the Budget In Brief. If you go to the Budget 2025 web page and click on “Lowering Costs for Manitobans” under related links you will be directed to another web page with a tile for “Personal Income Tax Changes”. If you click on that …. you won’t find it there either. That takes you to the prior year’s changes.

To find it, you have to dive into the Budget document itself, and scroll down to page 140 near the end of the document, and there it is: “Basic Personal Amount and Tax Bracket Threshold Indexation – frozen”.

An $82 million increase in income taxes over a full year, according to the budget document.

The Budget document notes that “for the majority of taxpayers, the impact would be $32 or less” for the 2025 tax year, but $82 million for a full year works out to an average of $130 per employed Manitoban to give you an idea of the impact. (The median tax impact would be lower.)

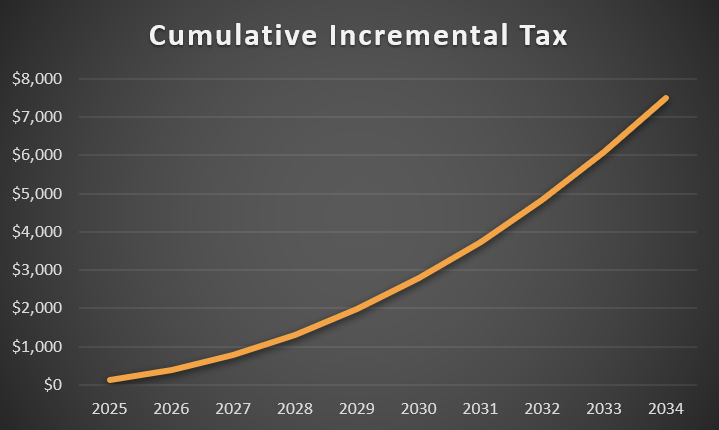

But that’s just the start of it: like interest, the impact of ditching indexing compounds over time. An average person that pays an extra $130 in taxes in year 1 will pay about $5,000 more, cumulatively, after 8 years (i.e. 2 full government terms) without indexing, assuming 2% inflation.

Any increase to inflation, as we know happens on occasion, will ramp up the compounding.

Now, the Budget document refers to the freezing of indexation as a “pause” which implies that it won’t last very long. I am not entirely convinced, because the former NDP government under Gary Doer and Greg Selinger froze tax brackets as well, and they did not get indexed again until 2017 after Brian Pallister took office.

I think much more likely is that this administration keeps the indexing freeze on, but offers occasional modest tax breaks — for example a one-time increase in brackets and/or basic personal amount, or a modest decrease in the tax rate in an election year. That sort of thing, while keeping the benefits of the tax bracket freeze. And I’ll bet that those tax breaks aren’t hidden on page 140 of the budget.

It is absolutely the government’s right to increase taxes if necessary. And people are open to increased taxes if they are justified. For example, after years of frozen property taxes there was a growing chorus of Winnipeggers saying “increase our fricking taxes already! Our roads are crumbling :( ” However, the lack of transparency with this particular strategy is disappointing.

I think if you were to ask any NDP MLA if they thought workers’ incomes should keep pace with inflation, I am positive they would agree. However they all voted for a policy that makes it much more difficult for take home pay to keep up.

Don’t let Adrien Sala or the Premier tell you they haven’t increased income taxes.

**EDIT 11/28**

Some have asked for clarity around what indexing means and there seems to be some misunderstanding about who this impacts:

Indexing means that the tax thresholds that define the rate of tax you pay on your income increases with inflation every year, so that your buying power does not erode with inflation. If your income increases 2% and the various tax brackets that your income falls within also increase 2% then your buying power stays relatively constant. i.e. your real (inflation adjusted) after tax income stays about the same.

If the brackets are frozen, then as your income increases with inflation more of your income goes to the government because more of it is taxed above the basic personal amount and taxed at a higher rate if you are in the middle or high income tax brackets, so even though your taxable income is increasing with inflation your after-tax income is not. You are becoming poorer. Your buying power is reduced.

This doesn’t just impact people who get bumped up a tax bracket as their pay increases. This impacts everybody who is earning more than the BPA because the proportion of your income that is taxed above the BPA increases vs the indexed status quo, and the proportion of your income in the middle or higher tax brackets (if applicable) increases, so you’re paying a higher percentage on that slice of income.

For those who say it still isn’t a tax increase, I would point out that the $ impact is exactly the same as keeping indexing in place and increasing the income tax rate. You can calculate that: by my math, over an 8 year span with 2% inflation the tax impact is about the same as increasing the tax rate by 1.3% for somebody in the middle tax bracket.

Other links:

The Canadian Press “credit rating agency S&P Global said earlier this year the province’s tax-saving measures are more than outweighed by the extra money being taken from the income tax change and the recent elimination of a property tax rebate”

Canadian Taxpayers Federation “On bracket creep, Manitoba stands alone.”

I don’t understand your calculations.

is misleading as an average person is not going to pay an extra $130 in taxes, an average person will pay approximately $34 at 10.8% of a $315 year-1 difference in the under $47,564 bracket. The budget indicates similarly (p. 143), citing $32 or less. In order to accumulate an extra $130 in taxes year 1 you would be making well over 100k and thus would be well above average.

jobbank.gc.ca indicates approximately 693.4k employed within the province, where a naive average would be $118.25 a head, but the govt defines the working population as aged 15-64 and the retired elderly still pay tax on CPP benefits, capital gains, and other forms of taxable income, likely skewing it lower.

I agree that it should have been more transparent.

Also, the year being nearly over has no impact on your tax liability, as it is assessed annually. The BPA being de-indexed in, e.g., May is the same as it being de-indexed now.

The budget document states the impact as $82M for a full year. $130 per person is a simple average based on their own number and a Stats Can labor market survey of Manitoba (630.3K employees in 2024). I had difficulty duplicating that calculation using 2% inflation, which is what the budget seems to assume for 2025 though I can’t find any reference for beyond that. I assumed I had some error in my calcs or that the gov;t was using a different inflation assumptions for 2026.

Agree the numbers don’t really seem to add up. Some more clarity around how they arrived at their published numbers would be helpful.